Warren Buffett has reportedly said that Return on Equity (ROE) is his favorite metric. That doesn’t mean it has to be your favorite metric, but ROE sees widespread use for good reason. Any serious student of fundamental analysis needs to know this metric and its limitations.

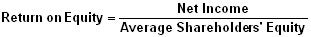

Mathematically, ROE is simple:

ROE is a true bottom-line profitability metric, comparing the profit available to shareholders to the capital provided or owned by shareholders. In a conceptual sense, it’s the profitability measure that equity investors care most about. Whereas return on assets (see the prior article by me) and return on invested capital each depict a variant of profitability available to both debt and equity investors, ROE stays pure, comparing the income available to just equity investors to the capital owned (and put to work) by just equity investors.

ROE: P/E’s Brother From Another Mother

If you’ve heard of the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio, you’ve seen ROE’s half-brother.

P/E, as we know, divides stock price by net income per share. For example, a Rs100 stock with Rs10 in net income per share last year would have a P/E of 10. We can compute P/E on an aggregate level, too: A company with a Rs100 million market capitalization and Rs10 million in net income would also have a P/E of 10.

If we flip P/E, we get E/P, or earnings yield. For instance, divide Rs10 million in net income by Rs100 million in market cap and you get a 10% earnings yield.

Now, just replace the market value of equity with the book value and you’ve got ROE. A market value of equity denominator shows how much a company earns per the value the market assigns it (a valuation concept), whereas a book value denominator shows earnings relative to the internal equity it had to work with (arguably closer to an operational profitability concept).

ROE: Betrayed by Book Value

Warren Buffett traditionally defined success for Berkshire Hathaway as an increasing book value of equity. It’s natural, if not axiomatic, that anyone who loves ROE trusts book value of equity. But there are many reasons not to trust book value of equity. Book value is reliable for banks, and sometimes for old-school “hard asset”-type companies, but if the goal is an accurate measure of operational returns, it can be problematic as the denominator for ROE in many situations, especially with modern business models and corporate practices.

We discuss some of those situations below. Note that for best comparison, adjustments need to be equally applied across the full comparison set, whether a company’s own prior financial history, competitors’, or both.

Factors that could skew book value of shareholders’ equity high (and thus ROE low)

|

Common adjustments (or notes)

|

| High cash balance | Remove cash from shareholders’ equity value and, ideally, remove interest income from net income, adjusting for tax effects. |

| Goodwill | Remove goodwill, or at least goodwill deemed excessive, from shareholders’ equity. Not all analysts would make this adjustment; their logic is that excessive payment for acquisitions is a company’s “own stupid fault” and that a company should fairly be expected to earn a return on what it bought. |

Factors that could skew book value of shareholders’ equity low (and thus ROE high)

|

Common adjustments (or notes)

|

| Buybacks | Because buybacks reduce shareholders’ equity, some analysts add back recent-year buybacks to offset. |

| Write-downs | Write-downs are usually done for good reason (and usually not often enough), so many analysts would consider them explanatory factors to be aware of more than accounting quirks to be undone. |

| Profit after a long period of losses | Cumulative profits, at least those not paid as dividends, boost equity as “retained earnings” on the balance sheet. Cumulative losses do the opposite: they lower book value. As with write-downs, meaningful negative retained earnings shouldn’t be reversed simply to get a more normal-looking ROE, but analysts should note they make the metric relatively less relevant. |

| Research & Development (R&D) costs | Since 1975, US companies have been required to expense, rather than capitalize, R&D costs. Capitalizing R&D goes beyond the scope of this article, but basically entails adding a multiple or partial sum of prior-years’ R&D expenses to shareholders’ equity (capitalizing means putting something onto the balance sheet) while swapping actual R&D expense for an amortized accrual version (based on expected life of the R&D asset) on the income statement. |

In terms of keeping the spirit of ROE, the net income and dividends are fine. There’s some accounting theory debate about which foreign currency costs should be on the income statement (i.e., affecting net profit) and which should get “buried” in other comprehensive income, or OCI (which, despite its name, is a balance sheet account), but we’ll sidestep that debate for now, especially because foreign currency adjustments tend to ebb and flow over the years. This leaves one real culprit: buybacks.

A buyback double-teams the ROE denominator by reducing cash and increasing treasury stock (a “contra” account on the balance sheet that reduces book equity) in a single whammy. In fact, the companies whose ROEs are most skewed by buybacks are almost invariably among the highest-regarded; they’re the companies that have earned enough cash over the decades to bankroll big share repurchases. Just know that ROE will overstate the here-and-now profitability of the equity capital at work for these companies.

ROE’s Silent Influencer: Debt

In a usage sense, rather than a computational one, the biggest weakness of ROE is that it ignores debt. Yes, that’s also its biggest strength, as we mentioned earlier. See, debt can be friend or foe. Higher debt will, if things go well, increase a company’s resource base and thereby its profits. Because debt financing is usually cheaper than equity financing, companies can enhance returns to shareholders by taking on debt in a sensible proportion (ranging from very high for a safe utility to nothing for a risky biotech). The problem with ROE is that it can’t differentiate between profitability boosts fueled purely by operational gains and those fueled by added leverage.

The Best Is Yet to Come

While ROE is the most directly relevant profitability metric for equity investors, many analysts contend that measuring profitability on an equity level has a few too many quirks and warts to be ideal. Their choice for measuring overall company profit? Return on Invested Capital, which we’ll discuss in the next section.

No comments:

Post a Comment